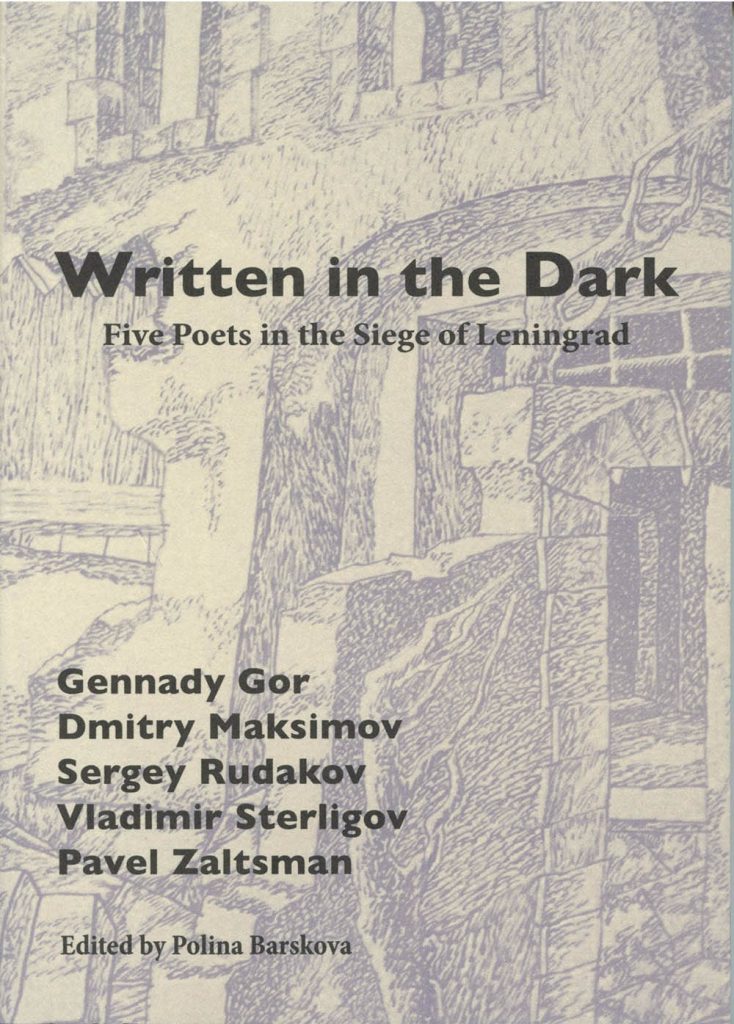

This anthology presents a group of writers and a literary phenomenon that has been unknown even to Russian readers for 70 years, obfuscated by historical amnesia. Gennady Gor, Pavel Zaltsman, Dmitry Maksimov, Sergey Rudakov, and Vladimir Sterligov, wrote these works in 1942, during the most severe winter of the Nazi Siege of Leningrad (1941-1944). In striking contrast to state-sanctioned, heroic “Blockade” poetry in which the stoic body of the exemplary citizen triumphs over death, the poems gathered here show the Siege individual (blokadnik) as a weak and desperate incarnation of Job. These poets wrote in situ about the famine disease, madness, cannibalism, and prostitution around them—subjects so tabooed in those most-Soviet times that they would never think of publishing. Moreover, the formal ambition and macabre avant-gardism of this uncanny body of work match its horrific content, giving birth to a “poor” language which alone could reflect the depth of suffering and psychological destruction experienced by victims of that historical disaster.

Polina Barskova, a Russian-language poet and scholar of the Siege, edited this volume from archival materials. The book includes an introduction by Barskova and an afterword by renowned literary critic Ilya Kukulin. The poems and supplementary materials were translated by Anand Dibble, Ben Felker-Quinn, Ainsley Morse, Eugene Ostashevsky, Rebekah Smith, Charles Swank, Jason Wagner, and Matvei Yankelevich.

Written in the Dark was named Best Literary Translation into English for 2017 by AATSEEL (Association of American Teachers of Slavic and Eastern European Languages).