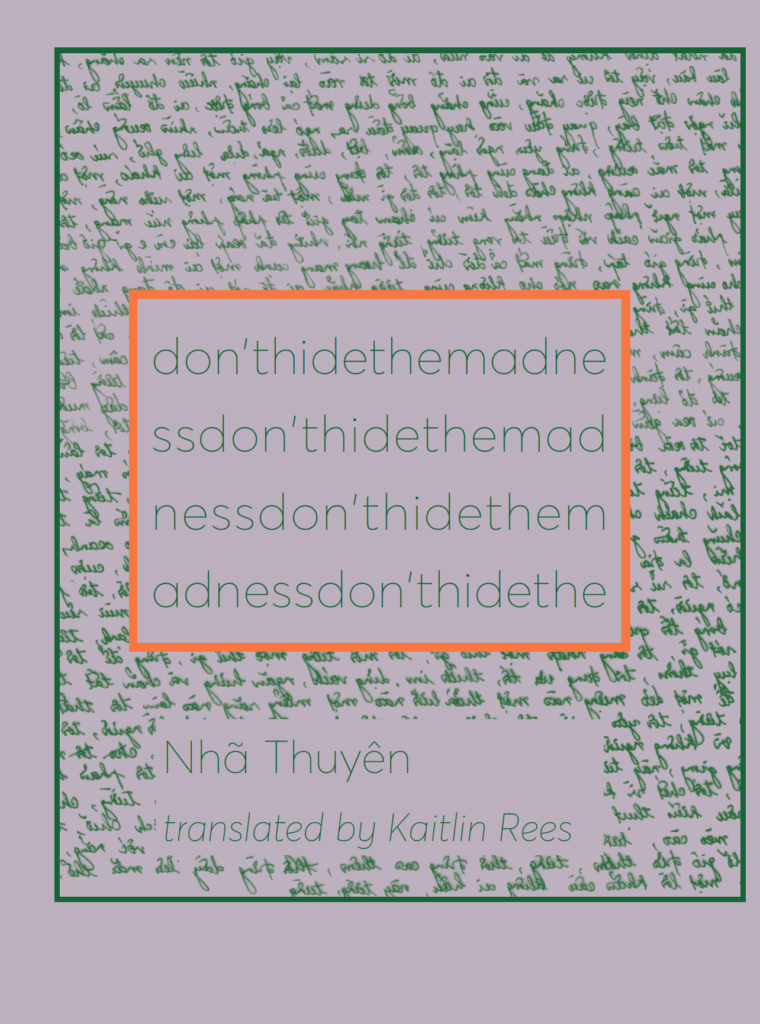

Nhã Thuyên refuses to let herself or her work be a symbol or token for anybody. Her work refuses all easy interpellations. It is a wall of words. It speaks through and against this wall. It faces this wall. It seeks to destroy this wall and to preserve it. Its language is wound round so tightly that one would think it would explode. Yet, precisely from this point, it expands, unfolds, unrolls into a breathtakingly expansive, excessive plenitude. It’s some of the most beautifully rigorous poetry in existence today and I am grateful beyond measure for its existence.

David Grundy

A beautiful curse of a book that suspends you in an ocean of dream and vision, where the world feels charged with possibility as thought after delicate and visceral thought of Nhã-Thuyên-through-Kaitlin Rees unspools itself as from a tight coil of paper around the fingers to demonstrate how a language might be renovated through a different one like a hermit’s ecstatic revelation too-easily called mad and once you see through the lie the book ends, that’s the beautiful curse of it.

Hao Guang Tse

This book condenses the madness we need to see in the world. The madness of language tightly unleashed. What if language is untethered from the containment of my language, your language, my work, your work, daytime language, nighttime language, ravishing language, suffering language, destroyed language, blood language? What if blood flows around and away from the old question of shared blood vs. separate blood? What if we let the foreign be kin? How to wind all the wounds into words? Despite or because of the wounds, the words of Nhã Thuyên and the transport of Kaitlin Rees are so vigorously, so carefully, rapturous and naïve. Their words move butterflyingly, hurricanically. They dialogue with walls. They slam themselves into walls. They play with moss. They listen to the cries of scars, the cries of rain. They keep asking what is the use of doing all this while they do it all anyway. They compulsively dream about everything that was and ever has been while also waiting for everything that was and ever has been to be washed clean by rain. A breath of distant rain. Nhã Thuyên and Kaitlin are two of my first, favorite, and ongoing teachers in writing, loving, and listening to the quiet echoes of distant rain while nursing the howling wails of our crazy human heart.

Quyên Nguyễn-Hoàng

Nhã Thuyên’s poetry revels in oneiric omens and reveals like Easter eggs to knowing readers. Her chapbook dedication to “dead fish everywhere” acknowledges her dissident forbears and contemporaries—poets cruelly deprived of their voices like fish deprived of oxygen, but their belly-up presence exposes the pollutants in the water, just as a prison wall may seem to trap a free spirit, but tường, the word for wall in Vietnamese, also means to tell one’s story, to have “a slab of broken limestone a stick of bamboo to scribble with.” In Nhã Thuyên’s linguistic shadow play, stars that rhyme with scars are also sao, the sparks of questioning that may explode or implode, while scars are sẹo, stigmata of deathless defiance. To read Nhã Thuyên’s poetry is to be leavened by “the fresh breath of distant rain that pervasively patters down each lunar cycle, whose shadow jumps out of the viscous black water...”

Thúy Đinh, bilingual critic and editor, Asymptote Journal and Da Màu Magazine

What hides inside of madness, inside of muteness, inside of drift or rain or silence? How do we learn to hear a “nighttime language” that communes equally with wall and the dead, that is cut off even from its own shadow, that cleaves toward darkness and barrier, waves and salt, that asks “how does a scar cry” or “how does a sound cry”? Nhã Thuyên’s poems speak to a speaking from deep inside, a “lin-lin-gua-gua” preserved inside of madness and/or muteness, a knowing of language as haunted, decried, divided, guarded, disassembled and reassembled, burbled and mangled, a language self-devouring and reemerging, and through all of these convolutions: surviving.

Dao Strom

"Language and I are a pack of stray animals," writes Nhã Thuyên in this wild onslaught of a book wonderfully translated by Kaitlin Rees. A lover of darkness like Kim Hyesoon, Nhã Thuyên is an elemental poet. The overwhelming momentum of her work comes from the drive of her never-ending sentences, which produce a productive, strong exhaustion not unlike those of Inger Christensen or Frank Stanford. The paratactical onrushing resembles the Pacific Ocean bashing the shore or, as this book describes, a Theresa Cha-like crawling into the tenebrous blindness offered by the cave of muteness.

Ken Chen

Nhã Thuyên’s poems are always in a thrilling conflict—be it with the tongue (the language), the tongue (the organ), or other seemingly non-absurd parts of our life: the idea of belonging, hair loss, or even a digital map. Insistent and fearless in its choices of form, intense and rebellious in its style and language, Don’t Hide the Madness gives all of us a minute with a poetic visionary and a translator who understands the vision.

Norman Erikson Pasaribu