We went off course but then I was brought back to my original point. We walked by the carousel under the bridge but then we returned and stopped in front of the carousel. We stopped when we heard a train passing over us over the bridge and then when it had passed over we all laughed, taking someone’s cue, and then we proceeded. We went ahead of everyone else and then the rest followed us a few blocks away. I realize I never asked myself, where are they now? I realize now I never needed to know where exactly are they? If I stop to ask myself now, I would have to guess that it would have been a city, but a mid-sized city, a city that was big enough to not feel like a town, but a city that was small enough where two people could meet in a way that you could follow from beginning to end.

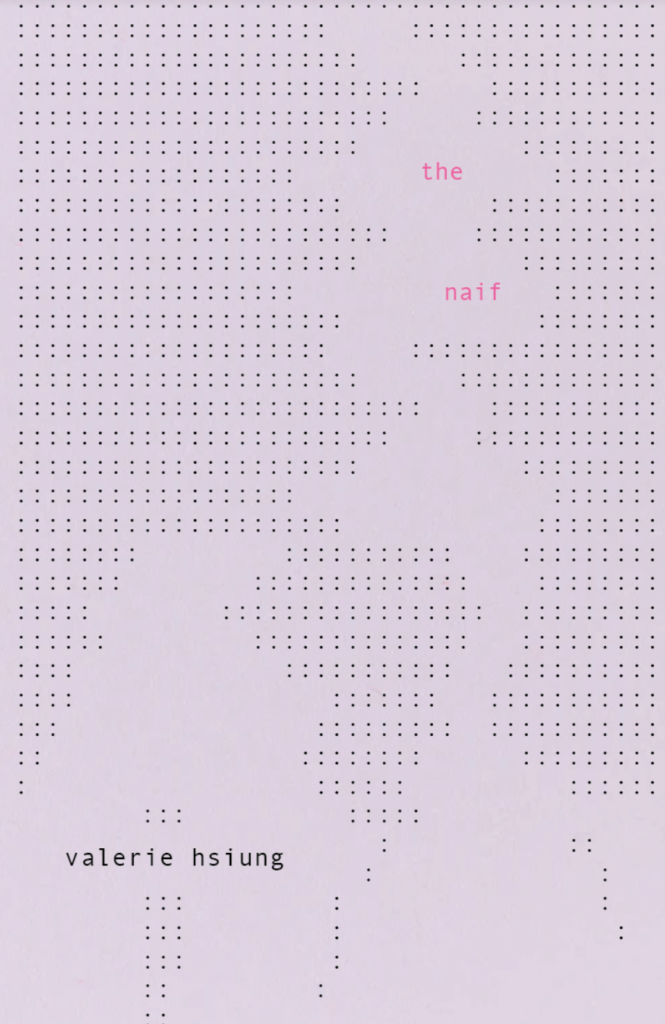

The Naif

Valerie Hsiung

May 2024

A philosophical rumination that pulls us all the way into its depths, The Naif is an abstract painting made of words and sentences and punctuation or lack thereof, a distant memory whose skin you get to touch and feel as you attempt to find your way through its centers and peripheries.

Poupeh Missaghi

The Naif lives in a practiced state of naivety—a language-fasted, resource-starved loop—and it lives as a test: of what awareness, what becoming, what imagination is possible under the scarcest of conditions, conditions that can make it impossible to deceive or beguile (others or oneself). It is a book as glass house reversed, where the person walking by can see all the way in, but the person inside can’t see halfway out—and yet the person inside has made this house. Perhaps because of the danger to the writer’s life that would result from any direct address to the Apparatus, the writer will have to commandeer the Apparatus’ own terms of ‘neutrality’ to forge a secret path and get word (past the Apparatus) into the right hands. As though she, a language worker, under the watchful eye of the Apparatus, has been forced to create these daily logs, to send news to the other world that all is ok. So she must be careful what she says and what she doesn’t; so she does her job, and yet leaves clues throughout: all is not ok.

About the Author

Valerie Hsiung is a poet, interdisciplinary artist, and the author of multiple poetry and hybrid writing collections, including The only name we can call it now is not its only name (Counterpath), To love an artist (Essay Press), selected by Renee Gladman for the Essay Press Book Prize, outside voices, please (CSU), selected for the CSU Open Book Prize, YOU & ME FOREVER (Action Books), and e f g (Action Books). Her writing has appeared in print (Annulet, BathHouse Journal, The Believer, Chicago Review, digital vestiges, Gulf Coast, The Nation, New Delta Review), in flesh (Treefort Music Festival, Common Area Maintenance, The Poetry Project), in sound waves (Montez Press Radio, Hyle Greece), and other forms of particulate matter. Her work has been supported by Foundation for Contemporary Arts, PEN America, and Lighthouse Works. Born in the Year of the Earth Snake and raised by Chinese-Taiwanese immigrants in Cincinnati, Ohio, she now lives in the mountains of Colorado where she teaches as Assistant Professor of Creative Writing & Poetics at Naropa.

Praise

Halfway between Kafka’s Singer and Melville’s Scrivener, Hsiung’s Naif wields syntax as both tuning fork and sensor, sounding a singular diphthong at once cosmic and quasi-comic. With minute adjustments to eyeline and plumbline, this naif induces us to perceive human interaction as at once present and potential, threat and promise, banquet and gambit, culture and cult.

Joyelle McSweeney

A philosophical rumination that pulls us all the way into its depths, The Naif is an abstract painting made of words and sentences and punctuation or lack thereof, a distant memory whose skin you get to touch and feel as you attempt to find your way through its centers and peripheries. The Naif is an attempt for “reconciliation” between what we try to do in life while we have “already gone off course,” while we navigate an intimate piece of clothing dangling on a chair, cheese, mouse, juice gone bad, a lamp, a gift shop, all the what and the who of the everyday guiding us toward the word “transcend.” Kneading a slippery “new way of life” into a shape that is shifting and grounding, Valerie Hsiung shares with us her being in and out of community, in intimacy and in selfness. She invites us to “conduct ourselves according to the pulse of each other without losing the pulse of ourselves” while we immerse ourselves in the pulse of her beautiful language offering.

Poupeh Missaghi

Is it innocence to think that if you hold onto something long enough (community, relationship, attention) the habitual will give way to the extraordinary? The “person of insouciance” relating this logbook narrative evolves through the willful and unsuspecting ironies that threaten to foil the aim of artists and revolutionaries alike. The Naif so deranges intention with particulars—that is, with wonder—as to turn everyday fact into speculative fiction. A new way of living may yet prevail, thanks to Hsiung’s encouragement, akin to the spores of a mushroom, or to winning the lottery, waiting for us all along, as though in advance of the beginning.

Roberto Tejada

Praise for Previous Work

Valerie Hsiung’s To love an artist is a work composed of dislocations--or rather, durations, expanses of dislocated voices, bodies, and narratives. It is a series of studies on ductility and leaching--what we are at our base and what we become when brought, whether violently or voluntarily, in proximity to others, other species of being, other modes of existing, other methods of naming: the lines we cross, “Language from bronze infects language from copper.” When the poet writes, “Today, I speak a language of brutes,” I read the enfoldment of the cruelty our collective and respective histories into the languages of our subjectivity. Any expression of self or free-ness or united-ness is laden with material and intentions that do not belong to us. We have been mixed forever, we have been poured and burned through borders always, and are ourselves burned and poured through. And that is why it is useful to invent forms for the expression of our alloyed selves, to be non-knowing. To love an artist presents a despondent, broken, scattered form. Yet, it pulses with nuance and engagement. It’s beautiful, irreverent, and dangerously incoherent. It stays with you when you’ve stopped reading it and puts your seeing in disarray. It nourishes and it fails and it teaches. This is a book of refusal. It is a cosmography written as metallurgy; it wants to be the dust and it wants to be the friction.

Renee Gladman

Mise en scène: Valerie Hsiung’s virtuosic, book-length psychedelia-against-empire—a poetics of obfuscation measured out among heteronyms, a devastating excavation of memory as linguistic matter, performatively picking the scab of phonic displacements, fleetingly renderable while impossible to untangle. [...] Taken as an ongoing whole, the rigorous arc of Hsiung’s work feels immediately improvised & obscure. Prose gives way to crisp lineation, pulsing with charm & tragedy in a tenor all her own. Hsiung possesses a thoroughness of vision & technique, as reckless as it is dazzlingly realized in a space between poetics-as-such & performance art. [...] With The Only Name, the reader encounters something close to the total risk of being. Through the conduit of historical materialism—upheavals of displacement reorienting a person or people’s total experience of grounding—mother tongues & discrete customs of the body must epistemologically contort. Regardless of whether the artist would pose her stakes as such, the book deals in bitter roots (an empire’s obliterative wake), chronicled in their own particular languages.

imogen xtian smith, The Poetry Project Newsletter

In the News

Links

Publication Details

ISBN: 978-1-946604-25-5

Trade Paperback

160 pp, 4.5 x 7 in

Publication Date: May 01 2024

Distribution: Asterism Books (US), Inpress Books (UK)