William Carlos Williams wrote “a poet thinks with his poem.” The wild propositions that are shot through every line of this work are, in a word,

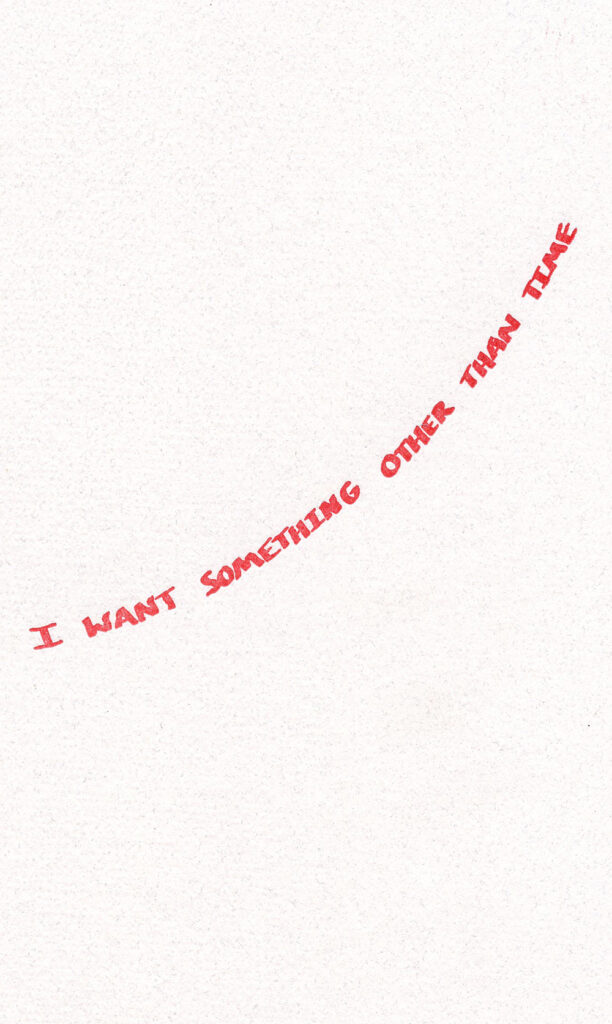

sensational. Freedman can turn on a dime from theory to agony, from politics to revelation, and then move to the open sky. In its way, I Want Something Other Than Time is a devotional book, if we consider the verticality of the mind opening to a larger order, devotional. This book is a tour de force.

Peter Gizzi

In this lake woodland region of poetry linked to earthen, jungle, and celestial isthmuses, and to the Oceans through the Sea, Lewis Freedman is like an apparition of the Sun, or like the glossy aspect of some ancient ferns. These thoughtful and heartful arrivals appear in ulterior faces, like rivulets of gentle wilderness running through every interior. He also knows death. So beware the Jaguar, and beware the small, beautifully colored poisonous frog. Panamá is near to where Lewis has been. Sometimes he makes an opening and I can laugh through it, even with him, or with one of his ghost envelopes inhabiting a companion space nearby. Each of these poems is a repetition of rupture and realignment, of an inquisitiveness that gets to the bottom of things guided by the purest water. The Hand Eye Symbolists of the Mississippi Era found a way to light these poems as guidance to navigate safely through our perilous futures. This book forms a perfectly spherical, luminous, geometric object in the palms of one's hands, like the ageless Mississippi stickball in its Higher Intuitive Mathematics from Indiana. Here is one of the languages from before when Mobilian was heard secretly in the wind. It is a Western cataclysm of a first link to evolve without intention, against the law in all the best ways.

Roberto Harrison

Not that poetry can be pure—more and more I am thinking the work of the poet today is metaphysical work. The poets I love, their poems sometimes appear to me as held within a vitrine of language, held away from them as much as to me, reader, moreso. "Nothing can ever be decently clothed enough to be read," Lewis Freedman writes. Lewis's poems make it possible to share in the heartbreak and embarrassment of his fluency and inventiveness as a thinker; one who knows the machine of his thought to be the poem. The dilemma, though, is this: the poem succeeds according to the ability of the poet to recede, so he must mark the characters for us to see; the book must be handmade. He pinches himself so he can keep going: Is this real? "Yes itself / to my voice says, / welcome to the precision / of a situation that doesn't / assume it." This book is astonishing, weird, and restorative.

Simone White