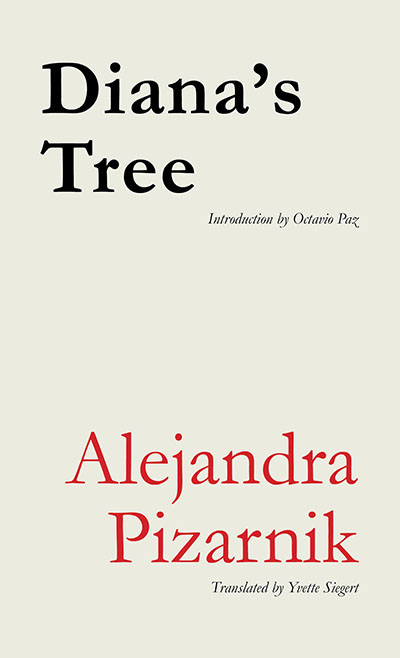

In 1962, Pizarnik published her fourth collection, Diana’s Tree, the book that would both change and establish her poetic voice, and it contained the slimmest verses the poet would ever write. It also carried a glowing introduction by Octavio Paz, who by that point served as a prominent Mexican diplomat in Paris and had become a leader of the city’s expatriate literary circles. Diana’s Tree, wrote Paz, was a feat of alchemical prowess, a work of precocious linguistic transparency that let off “a luminous heat that could burn, smelt or even vaporize its skeptics.”

Pizarnik would live for only ten more years after the publication of this book, but her work would undergo several radical stylistic transformations, from the luminous lyric that captivated Paz to the dense, anguished prose poems of Extracting the Stone of Madness, to the more dialogic, sometimes absurdist structures of her mature work. When Pizarnik committed suicide, at the age of thirty-six, critics had already compared her to Sylvia Plath, and likened the scope of her literary influence to that of Arthur Rimbaud or Paul Celan. Forty years after her death, Pizarnik retains a prominent place in both critical and popular assessments of twentieth-century Latin American poetry.